Amendment 1 is on the ballot: How will it affect redistricting reform?

October 31, 2020

There’s more to Nov. 3 than the national and statewide elections. On Election Day, Virginians will make a consequential decision that may affect our state’s politics for decades to come.

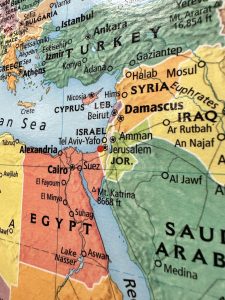

In spring 2011, Virginia state legislators prepared to vote on new state and congressional maps. The Commonwealth, along with 28 other states at the time, gave all redistricting power to the governor and the legislature. This system has created a unique issue in our electoral system for centuries. It’s called gerrymandering, where the mapmaking process is controlled entirely by the party in possession of the state legislature.

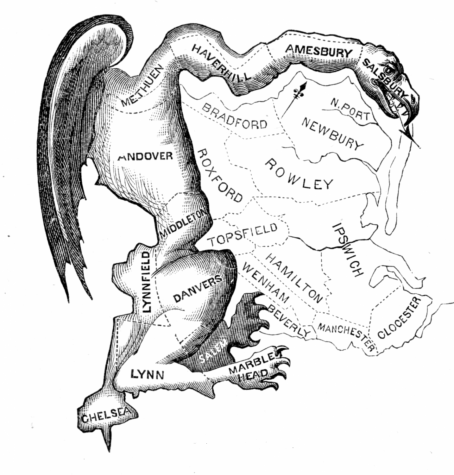

The founder of the gerrymandering system was Elbridge Gerry, who used his position as governor of Massachusetts to create an oddly-shaped map in 1812 (dubbed the “Salamander” by a Federalist newspaper”).

This system has been in effect ever since.

Following the 2010 midterm elections, Republicans maintained their hold on the legislature, and Bob McDonnell delivered the governorship to the party. There was nearly unanimous desire among legislators to create districts that would maintain the 8-3 Congressional balance, and a party trifecta made it within reach.

This led to the hiring of Thomas Hofeller, a redistricting operative that had already worked in several other states. Hofeller eventually aided in drawing districts geared to favor state Republicans on the state and national levels.

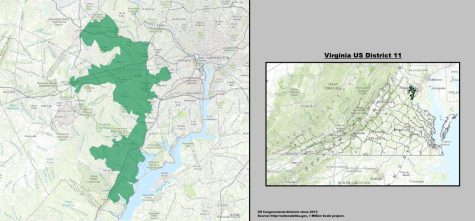

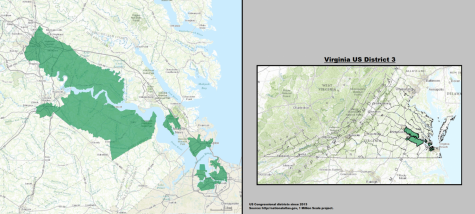

The 11th District in the Northern Virginia Region was created to safeguard Rep. Gerry Connely (D). This district, which combined Democratic constituencies in Fairfax and Prince William Counties, was drawn as a compromise to make then-incumbent Rep. Frank Wolf (R) in the 10th Congressional District. The 3rd District had the sole purpose of packing Democratic voters in Richmond, Newport News, Hampton, Chesapeake and Norfolk into one district. This uncompetitive map remained in place until the 3rd District was struck down as racial gerrymandering by the courts.

Does Amendment 1 symbolize the fight against gerrymandering?

After Democrats regained the governorship in 2013 and the Legislature in 2019, the balance of power shifted. Regardless, this has not changed the situation at hand. Under the current process, a party trifecta will draw districts that will likely be detrimental to those out of power.

This is where the proposed Constitutional Amendment 1 comes in. If approved by voters in November, partisan control of the process would be replaced by a commission of legislatures equally manned by Democrats and Republicans. In addition, a group of retired judges will choose the panel of eight citizens. This panel would hypothetically preside over the process and assist with mapmaking. This entire committee would work together to create fair maps that would then go to the Legislature and finally, the governorship.

Amendment 1 is officially endorsed by the Virginia Republican Party and opposed by their Democratic counterparts. Republicans, who had previously controlled the full legislature since 1994, argue that nothing is in the way of Democrats using their newfound power to gerrymander a map favorable to themselves. They also point out that Democrats, who have been running on enacting redistricting reform for decades, have flip-flopped on Amendment 1 after initially giving some measure of support.

Most state Democrats, including an overwhelming majority of minority lawmakers, argue the amendment doesn’t go far enough in taking mapmaking out of the hands of politicians. They have also accused Republicans of still supporting partisan gerrymandering, given Virginia’s history in the matter.

Consequences of an amendment ambiguous in nature

While in the minority, most of the Democratic caucus supported Amendment 1 in 2019. They proceeded to reverse their position by declaring themselves against the measure in June 2020. However, it’s entirely possible that this amendment won’t do enough. Redistricting would still be decided and voted on by a commission of legislators.

State Democrats have also raised the fear that Republicans on the commission will refuse to accept any map and force the decision into the hands of the Virginia Supreme Court, which currently has a 6-1 balance of Republican-appointed judges.

According to public polling, support for the amendment started out strong but has begun to dwindle as the election has neared. Virginia voters will weigh several of the following existential questions this November.

Is passing Amendment 1 the right way to go? Can Amendment 1 bring change to a century-old system?

If the amendment fails, there is a chance state Democrats will create a favorable map for themselves, thus continuing the system. Will Democrats break their word on redistricting reform by attempting to pass a gerrymandered map, or will Republicans attempt to use Amendment 1, should it pass, as a loophole to force matters to the Virginia Supreme Court? Voters are faced with a choice that, either way, has the potential to render significant consequences for the decade ahead.