Be Mindful of Mindfulness: A Case for Heightened Consumer Awareness During a Time of Crisis

March 5, 2021

Mindfulness—a concept that has established a niche for itself in mainstream health culture, could be an ally for students and teachers in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, significant contradictory information must make us reconsider our role as consumers of an increasingly vague and exaggerated mindfulness market.

The implications of the pandemic on student wellbeing are quantifiable. According to a week-long survey conducted by SurveyMonkey in August 2020, out of a sample size of 890 students, 61% noted that they were worried about falling behind in their studies due to the starkly different school environment this past year, with 40% of respondents stating that they felt more lonely than usual due to increased distance from the school community. The stressors of the virtual learning environment extend to future plans as well, with 50% or more of respondents noting that they are very or somewhat worried about losing scholarship opportunities and impeding on job and college aspirations.

These findings were echoed by the Sleep and Mental Health Amidst the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic report, which found that teens and young adults had the worst sleep quality and the highest rates of feeling depressed after conducting a survey with a sample size of 69,047 global Sleep Cycle app users since the onset of the pandemic.

However, students aren’t the only ones contending with the effects of the pandemic. As LCPS teachers prepare to open their classrooms to all the students who selected the hybrid option for the second semester on March 3, it is imperative to consider the ways in which they can be supported on the frontlines. A report published by EdPolicyWorks at the University of Virginia and the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies focusing on teachers in Louisiana found that 85% of teachers were worried that students would come to school sick, while more than half of the teachers fear that they will have to come to school while sick. Furthermore, the report found that teachers are also contending with the expenses of supplying their own personal protective equipment, with 1 in 5 teachers spending their own money on face masks and cleaning supplies.

The culmination of these burdens that are exclusively outside of our control has pushed society to look for outlets of alleviation, and one face has made itself familiar amongst the crowd of resources: mindfulness.

Mindfulness has gained immense traction since the pandemic started. The Holistic Life Foundation, a non-profit organization in Baltimore, increased their student enrollment in mindfulness education programs ten-fold, skyrocketing from 10,000 students in 2019 to over 100,000 this past fall. Teachers have also turned to mindfulness, for Headspace for Educators, an app focused on guided mindfulness exercises, saw a 77 percent increase in teacher sign-ups from mid-March to November 2020, as reported in “The Hechinger Report.”

Amidst this growing movement of mindfulness, it is easy to get lost. There are a lot of mindfulness resources out there that have exploited the Buddhist practice of distancing oneself from limiting attachments to the self and instead practicing compassion, to obtain profits.

In fact, the mindfulness industry in the U.S. alone is worth 1.1 billion dollars.

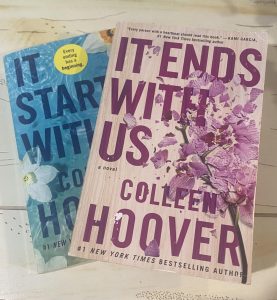

Even apps as well-known as Headspace have conflicting and currently weak data to support the scientific validity of the bold statements they broadcast on their websites. According to a 2020 literature review, 6 out of 8 studies supporting the app Headspace included in the review followed less than 100 people. The same review concluded that out of the 1009 wellness and stress managements apps that were included in the study, only 2.08 percent were supported by peer-reviewed evidence.

In a 2017 study published in “Perspectives on Psychological Science,” concludes that the pool of empirical evidence used to support the use of widespread mindfulness practices is riddled with poor methodology, including a lack of control groups, and varied definitions of what mindfulness practices actually constitute.

A 2014 review that included 47 meditation trials and a subject pool of 3,500 participants yielded no evidence that pointed to any improvement in attention, sleep, weight gain, or substance abuse abatement, as reported in Scientific American.

It has also become tempting to lean on mindfulness practices as a therapy method. However, it was observed in a 2015 study published in “ The Lancet” that mindfulness practices were no more effective at preventing relapse than existing antidepressant medications.

Furthermore, it is argued by Ronald Purser in an article published in the Guardian that the current tone of mindfulness marketing is set to the wrong tune, for it encourages a fixation on the self, rather than encouraging a compassionate mindset.

This is why it is important to acknowledge that the mindfulness market doesn’t provide a blanket solution or product that we can get behind. However, that doesn’t mean mindfulness should be completely abandoned either.

A 2014 study published in “Frontiers in Psychology” conducted a retrospective study that identified twenty-four studies, 13 of which were published, and analyzed the effects of mindfulness with a sample size of 1348 students between grades 1 and 12, 876 of whom served as the control group. A cautiously optimistic conclusion was derived, stating that the mindfulness-based interventions could help in improving cognitive performance and increasing resilience to stress. However, the researchers noted that due to variability in the study samples and implementation approaches, isolating the effects of mindfulness is difficult.

In a study done by a team from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a small group of sixth graders at a Boston charter school went through eight weeks of mindfulness practice, for 45 minutes, 4 days a week. The students who participated in the activity showed improvements in how they perceived stress and in their attention span. The mindfulness group also underwent a brain scan, which revealed that everyone in the mindfulness group showed a lessened reaction in the amygdala, the region associated with emotion, when shown pictures of fearful faces. However, the researchers described the improvements in attention as “modest,”and found that at the end of the study, the treatment group’s Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale score did not improve by the end of the academic year.

So is it even worth spending the time or effort on mindfulness practices? That question is reserved for the individual to answer. However, we do believe that the core of the mindfulness practice has been tugged in many directions, with each hand promising to show you the way to a fail-proof coping mechanism. During this time, the educational community, along with the rest of the world, must be supported with resources such as mental health counseling and training for teachers to help intervene when students need help. But in order to circumvent the trap of the hyperbole-charged mindfulness industry and flocking to certain pieces of merchandise, we must arrive back at the original purpose of mindfulness: to be aware of one’s thoughts and emotions in the moment, free from self-inflicted judgement. It is not meant to be an escape, like a hobby, or a cure. Its effects change based on the individual’s experience. Instead of focusing on lazily standardizing mindfulness, educational material on mindfulness practices, the good and the bad, should be distributed throughout the community. Mindfulness should be released from the current connotations, and instead take on a more open-minded viewpoint that encourages compassion towards everyone, instead of a means of focusing purely on oneself.