In July of 2024, Gov. Glenn Youngkin signed Executive Order 33 that stated all Virginia schools will implement “Bell-to-Bell” cell-phone free instructional time to prioritize students’ mental health and education. This means that from the time the morning bell rings, students will have shut off their phones and will not access them until the final bell.

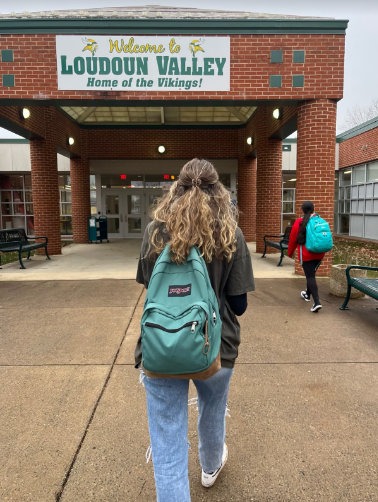

Just a month before that, however, the Loudoun County School Board passed its own policy limiting student phone use. Though similar, the LCPS policy does not require phones to be put away during lunch or in-between periods. As the board reviews the results of this policy, it is possible changes will be made to phone restrictions in the future.

The idea is that because students will not access their phone, they won’t feel tempted to check notifications and, therefore, will be able to focus on school and face-to-face connections.

But as well-intended as phone restrictions are, they’re far from the cure-all policy-makers, teachers and parents hope them to be. Here’s why:

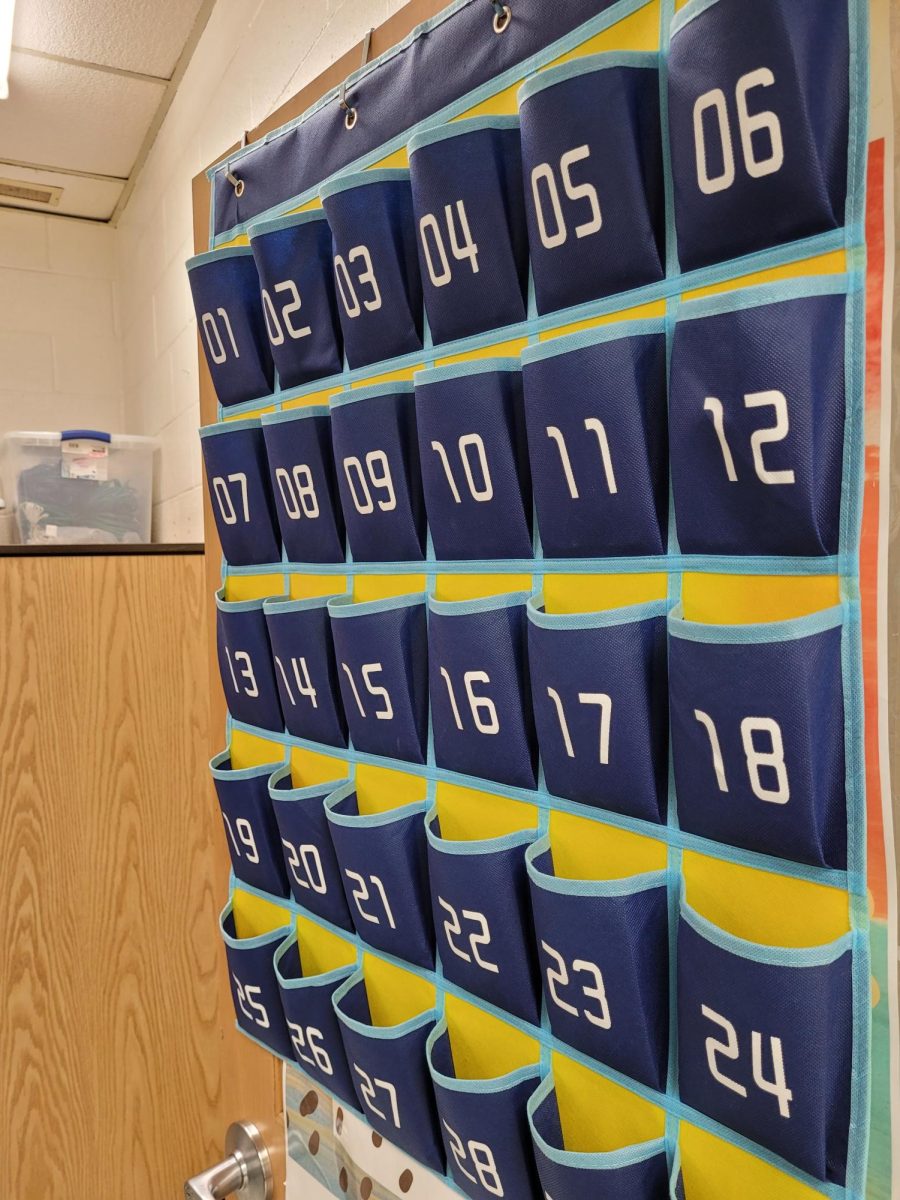

Difficulty in Enforcement

The first hurdle is the enforcement of the policy. In order to truly create a “cell phone-free education,” every teacher in every classroom — in every hallway — must remain firm on the restrictions, ensuring every student puts their phones up and away at all times.

This, as any Valley student knows, is not what’s happening. Many teachers are not strict on the policy, or have become more lenient as the year has gone on. For many students, it’s as if the policy were never in place at all.

Of course, the reluctance to enforce the policy is more than understandable. Students can and will find ways to resist restrictions on their phone use — whether that means bringing additional devices, lying about bringing a phone to begin with or simply refusing to stop using their phones.

By high school, students are well beyond the age where rules and restrictions are accepted without question, far beyond the point where mere scolding is enough to get them to behave. Students want independence. And in order to help raise responsible, functioning adults, schools need to give older students the freedom to make their own decisions.

Any limits on that decision making, however beneficial to students’ well-being, are certain to breed resentment and rebellion.

Addressing the Root Problem

Breaking students’ dependence on phones can’t be done by force alone. These bans, while they help to begin the conversation around teen phone use, are limited in their ability to address the root of the problem and create long term, healthy habits.

Even if the school day is completely free of phones, the second the final bell rings, students will get back on their devices. This ban on phones doesn’t solve the unhealthy habits, it just postpones them and pushes them out of sight.

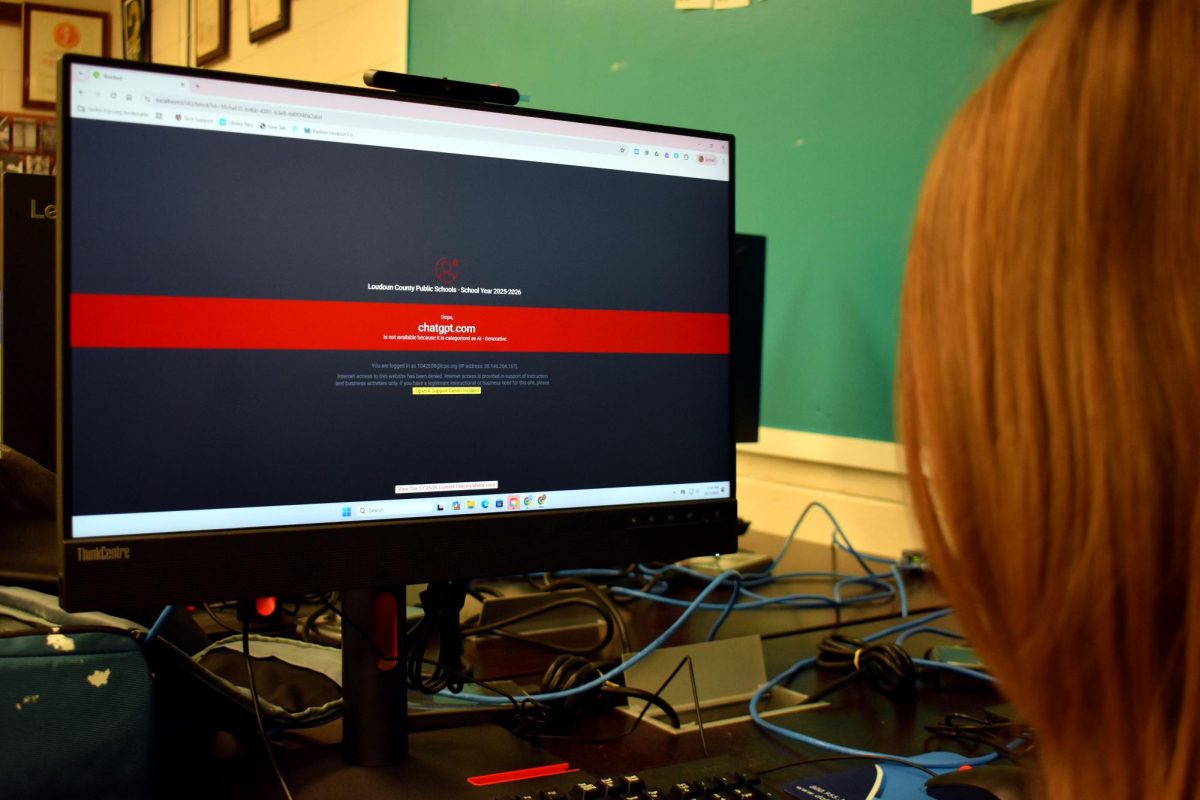

We are up against corporations who have nearly perfected the art of monopolizing our attention for their own profit, social media sites that simultaneously create stress and provide an easy escape from it. The solution to a problem like this, then, is a communal one, one that requires a change in culture as much as it requires a change in behavior.

People gravitate towards social media because they believe it provides something they are unable to find in real life — namely, community and entertainment.

To address students’ excessive phone use, connection-building must be part of a school’s strategy. After all, the best way to get students to participate is to give them something they want to participate in.

Of course, changing the entire learning environment of a school is easier said than done, but initiatives like Engage IRL have been launched in other states in pursuit of this very goal. A greater emphasis on extracurriculars, an active school community, a less stressful workload — all these things can help students want to be more engaged at school.

The key here is not to demonize phones, but to decentralize their place in our worlds — acknowledging they have their uses, but should not dominate our lives.

This, too, allows us to see the other issues affecting student learning outside of phones. It’s not always that students are stressed because they’re on their phones, sometimes we’re on our phones because we’re stressed.

Conclusion

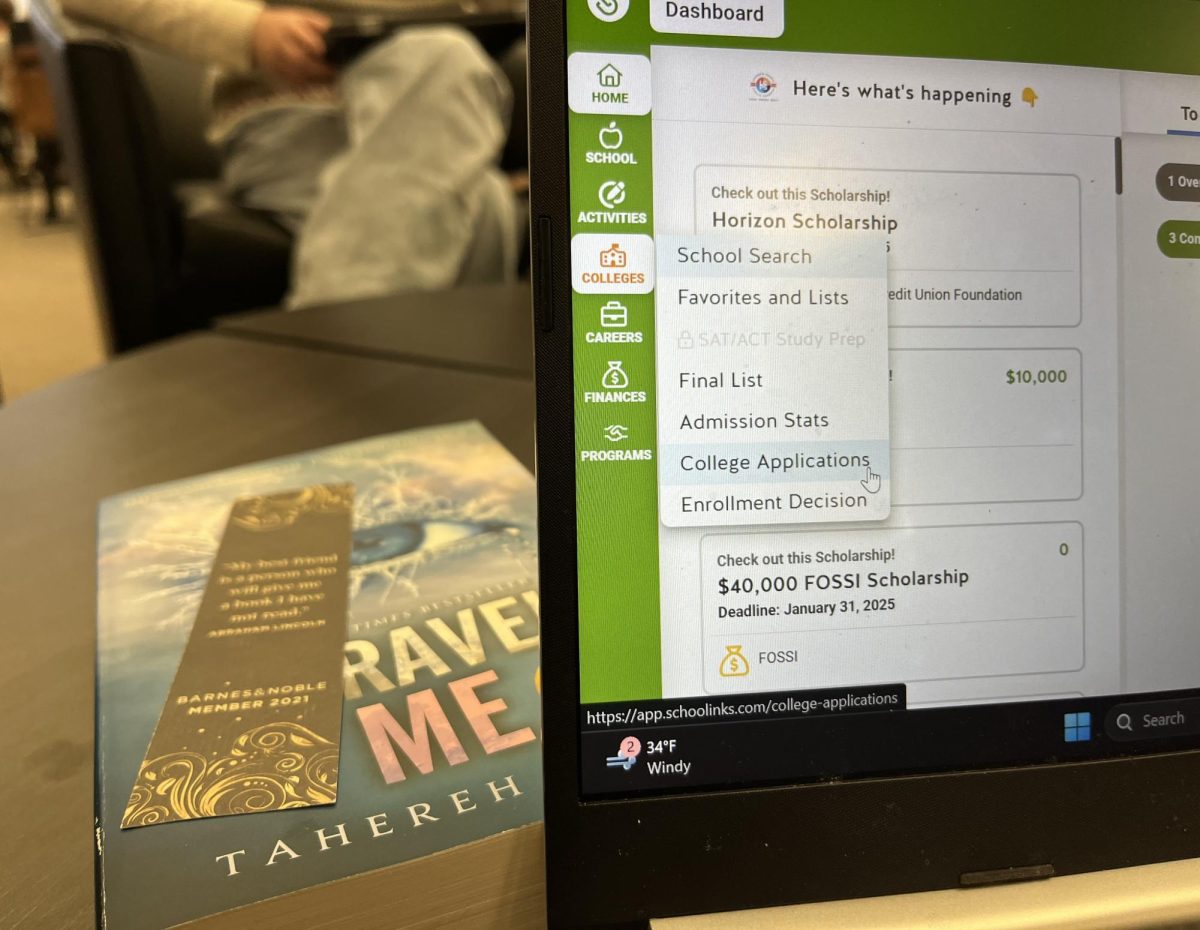

If the intention is simply to get students to pay a little more attention during class, sure, these policies work well enough. And a ban is definitely beneficial for middle school and younger students. But it doesn’t necessarily help high school students become responsible.

In the future, students will have to regulate themselves and, given that high school is preparing students for the real world, students have to be allowed to make their own choices.

It’s the role of the school to facilitate an environment where students are motivated to make the right ones. A student can’t be forced to put down their phone, forced to learn, forced to pay attention, but they can be inspired to, motivated to.

A phone policy is nothing but a start.